There's Still Christianity in the Public Schools?

Jewish public school students down South contend with missionary classmates

By Jan Jaben-Eilon, JewsOnFirst.org, October 2, 2012

It's not easy growing up Jewish in the Bible Belt, although Jewish youth report that their Christian classmates in public high schools can often be caring - in their own way. "A lot of classmates said they'd pray for me since I was going to hell because I'm Jewish," said Hanna, now a college sophomore. "Once I was asked if I had horns or had shaved them down," recalls Jane, who attended a different public high school in the metropolitan Atlanta area. "The kids weren't mean. One said that it was so cool that I was Jewish, and asked if I was thinking about converting. Her tone changed, though, when I told her I wouldn't convert."

Another student recalled, "One of my best friends belonged to an evangelical Christian church and she tried to get me to go to church with her, not very subtlety. Just after she returned from a religious retreat, she told me that I should accept Jesus because 'I don't want you to go to hell.' I responded that I'm Jewish and that's it. She never mentioned it again. But there was another sweet girl and it got back to me that she said it was too bad that I was going to hell because she really liked me." What partly bothered this former student was the sheer "innocence" of the comment: "That's what she was taught."

All three of these former high school students were raised with a strong Jewish foundation so they were not easily tempted by the proselytizing peer pressure from the public school pupils surrounding them. But for more vulnerable, less knowledgeable Jewish youth, the attempts to draw them to Jesus can be jarring - and sometimes, even successful.

Some children lost to conversion

"We have a struggle in the Jewish community," says Rabbi

Fred Greene of Temple Beth Tikvah in Roswell, a northern suburb of Atlanta. "Parents send their kids to

religious school, but don't want them to be religious. Then parents come to me" when their child is

tempted by their Christian peers, and "usually by the time they tell me, it's too late." Too late? "We

have lost some of the kids of our congregants" to conversion, he admits, solemnly. "It's a painful thing

for the families."

While few other rabbis we contacted reported similar disheartening consequences of susceptible youth being exposed to aggressive evangelical friends, there is a real problem in the public schools in the Southeast. "I'm encountering it far more here than in New York or Connecticut," says Greene, who previously worked in congregations in those states.

"This is the most religiously diverse country in the world, with more churches per person," says Debbie Seagraves, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Georgia. "It's a rare month that we don't get at least one student complaining about proselytizing in a public school."

Southern culture of religion

Shelley Rose, associate director of the Southeast office of the

Anti-Defamation League (ADL), attributes the fact that she gets calls regularly about the same issues,

to the culture of religion in the South. "And it happens in the metro Atlanta area, not just in the

rural areas," she says.

But what are the issues emanating out of the public schools in the increasingly evangelical South? Although it's prevalent, proselytizing by other students in the public schools isn't the only religious reminder that Jewish youth are in a minority and cannot ever truly be a part of their peer group.

"It can be the little stuff, like my classmates wishing me to have a 'blessed day'. I know that really means that Jesus blesses you," says Jane. "I have a friend who introduces me as her 'Jewish friend, Jane'. It's always in your face. Not a day goes by that I'm not reminded that I'm a Jew."

And Jane has something to compare this experience with. She moved from heavily Jewish South Florida when she was 12 years old. "I never knew I was in a minority in South Florida; it was so normal. My friends were either Jewish or understood what that meant. In Georgia, there were classmates who had never met a Jew before."

Jane's mother, Barbara, recalls how difficult those years were for Jane. "She really had to fight for her identity to be Jewish and she'd never had to do that before. She would come home upset with her little voice, but I have a much bigger, louder voice."

One day Barbara received a call from the school, complaining that one of her children was absent that day. "It was either Rosh Hashanah or Yom Kippur and my husband Alex responded, 'You should know why he was out of school, that it's the most holy of holidays.' The vice principal said he had to write a note for my child to get an excused absence and Alex just refused."

Both Barbara and Alex grew up in New York and South Florida and although they've lived in the Atlanta area for more than a decade, they are still not accustomed to the fact that here it is an issue to be Jewish, and it shouldn't be. "You shouldn't have to explain who you are," Barbara says.

When Jane graduated from the University of Georgia in Athens earlier this year, the governor of the state referenced religion in his address. "My son about flipped out," says Barbara. "I went to two other college graduations for my children and there was no reference to religion there."

But none of this is shocking to Jews who have lived in this region for years.

"It's always been this way."

"I've lived in Georgia for 64 years," says Seagraves, who is

Jewish. "And it's always been this way. A lot of Christian practices are incorporated into schools

inappropriately."

Rose reports that the calls to her ADL office increase right before the High Holidays, because of concern over either excused absences or teachers scheduling exams on the holidays. Calls also come into the office in the late fall as the Christmas celebrations start, and in the spring before graduations, which may be held in a church, or baccalaureate services, which are, by default, religious.

Christianity seeps into the South's public schools on several levels. A former football coach, Rick Gage, leads the Duluth, Ga.-based GO TELL Ministries under whose auspices he presents anti-drug or anti-sex speeches in schools that have underlying Christian messages. Its website states: "The purpose of GO TELL Ministries is to reach as many people as possible for God's Kingdom."

The Fellowship of Christian Athletes has clubs in just about every high school in the area.

As long as the religious clubs are run by the students themselves, there is generally no legal issue. But it's not always clear cut. As Seagraves points out, "Everywhere you go in this state, you will find problems that border on being unconstitutional."

Stealth evangelism

It's the borderline not always being apparent that is the problem. One

parent relates how his son would eat breakfast in the school cafeteria when a group of athletes would

come in and "perform" for the students. "They would basically lift weights for about 30 minutes," then

go to the microphone and "announce that Christ helped them become athletes. After five or 10 minutes of

sermon, they would pray and leave," but meanwhile the students eating breakfast were not allowed to

leave the cafeteria and were obviously a captive audience with no option to "not hear."

Rose refers to these situations as "stealth evangelism." She recalled that once a magician came to a school. There was a teaser during lunch and the students were invited to the magic show after school. The second half of the show was proselytizing and some Jewish kids bought the magic kit in which they found proselytizing materials.

In another case, a cheerleader complained to the ADL that before football games the coach would lead prayers.

Despite the myriad examples of this quiet - or not so quiet - proselytizing, most children and most parents never speak up. "Not one-tenth of one percent even writes us a letter," ACLU's Seagraves says. "It's often not safe to speak up. Parents just want their kids to be safe and not hassled so that they can learn. It takes a unique kind of courage to make a complaint. It must be a family decision."

Creationist stickers in Cobb County

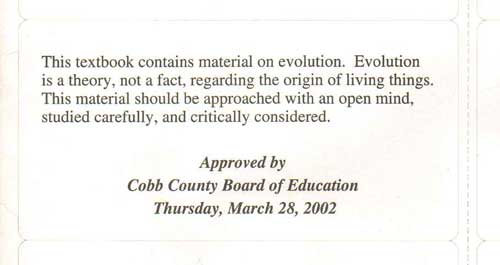

In 2002, one Jewish family was brave enough to speak out

when Cobb County schools placed stickers in their biology textbooks with a disclaimer that stated,

"Evolution is a theory, not a fact, concerning the origin of living things." Jeff Selman as well as

other Jewish parents of children in the Atlanta-area schools claimed the stickers violated both the

establishment clause of the U.S. Constitution and the separation of church and state clause in the

Georgia constitution because, they said, the purpose and effect of the stickers were to cast doubt on

the scientific consensus regarding evolutionary theory in order to promote religious beliefs in the

schools.

Indeed, in the past, saying that evolution is theory and not fact has been used as a tactic of creationists and intelligent design advocates. But teaching creationism and intelligent design in schools has been found by courts to be a violation of the establishment clause which forbids governments from endorsing religion. The case of Selman v. Cobb County School District was eventually settled out of court in favor of the plaintiffs and the judge ordered a permanent injunction against Cobb County schools from disseminating the stickers in the textbooks or any other form.

Selman is now a voluntary Atlanta chapter president of the Americans United for the Separation of Church and State (AU), a nonpartisan educational organization dedicated to preserving the constitutional principle of church-state separation. When he saw a billboard for someone running for the Cobb County school board pledging to bring back the stickers, he notified the AU Washington, D.C. office and an attorney there wrote a letter to the school district reminding them of the injunction and that it would cost them a lot of money if the stickers were returned to the textbooks. Very quickly, the advertisement was pulled, Selman says.

Oftentimes, all it takes is a letter from an attorney, warning a school or school district of the legality of a certain situation. "We try to resolve issues without taking action," says Ian Smith, an AU staff attorney. Those issues are brought to the AU generally through the chapter volunteers, like Selman, from around the country. Usually the question is whether there's been a violation of the law.

"In the South, religion is pervasive and some people just ignore the laws," says Smith. "My general sense is that it's becoming worse because it's becoming politicized. Politicians are getting people riled up," implying or outright suggesting that there's a war against religion today. "This tends to lead to a backlash and people do more things that are illegal."

Problem worse in rural areas

In rural Paulding County, west of metropolitan Atlanta, the

Americans United chapter president is Ryan Hale, a Baptist minister and former teacher. In his opinion,

the "religious right has co-opted the Baptist message of separation of church and state. And the problem

is worse in the rural area because people don't know their rights and the majority is evangelical and

feels they can do whatever they want."

He cites reports of Catholic students cornered in hallways by fundamentalists, and being told they were going to hell, or a teacher inviting students to after-school bible study classes in the classroom, or speakers with religious themes invited to school assemblies in South Georgia or a football coach bringing in a youth pastor to talk to the students about their relationships with God. The latter was stopped after the AU wrote a letter to the school, says Hale who is considered a pariah in the Southern Baptist community because of his defense of the separation of church and state.

Of the complaints that are brought to AU's attorney Ian Smith, "I can dispose of 90 percent by myself. There are no violations. But the remaining 10 percent are clearly violations or judgment calls that go to senior lawyers, and can be passed up the chain for possible litigation. We have maybe three to five new cases a year."

According to Marc Stern, general counsel for the American Jewish Committee in Washington, D.C., the law "permits much that Jewish parents don't like. But the law also protects. Jewish parents are often seeking something the law can't provide."

Although AJC's Stern reports that he is fielding fewer complaints about religion in public schools, Charles Haynes, director of the Religious Freedom Education Project of Newseum in Washington, D.C. contends there is "more religious expression in schools than there has been in decades. In the mid- to late-80s, there was very little student religious expression. However, especially in the Southeast, and in the rural areas, there was still school-sponsored religious expression, even after the Supreme Court ruling."

It was in the early 1960s when the U.S. Supreme Court handed down landmark rulings striking down government-sponsored prayer and Bible reading in public schools. Fifty years later, many Americans still hold the mistaken view that these Court rulings prohibited students from expressing their faith in public schools. But the Court did not eliminate prayers or the Bible from public schools, the AU explains. Rather, the rulings barred state-sponsored religious practices, including devotional use of the Bible by public school officials. More recent conflicts have involved differences about the limits of student religious expression.

The Supreme Court addressed this issue in 1990 when it upheld the Equal Access Act that became law in August 1984. According to the Supreme Court, Congress passed the act to end "perceived widespread discrimination" against religious speech in public schools.

The Nashville, Tennessee-based First Amendment Center says that while Congress recognized the constitutional prohibition against government promotion of religion, it believed that nonschool-sponsored student speech, including religious speech, should not be prohibited in the school environment. In a discussion of its own guidelines, which achieved buy-in from a broad spectrum of groups, The First Amendment Center further explains the three basic concepts of the Equal Access Act.

The first is nondiscrimination. If a public secondary school permits student groups to meet for student-initiated activities not directly related to the school curriculum, then it is required to treat all such student groups equally.... This language was used to make clear that religious speech was to receive equal treatment, not preferred treatment.

The second basic concept is protection of student-initiated and student-led meetings. The Supreme Court has held unconstitutional state-initiated and state-endorsed religious activities in the public schools.... However, in upholding the constitutionality of the act, the Court noted the "crucial difference between government speech endorsing religion, which the Establishment clause forbids, and private speech endorsing religion, which the Free Speech and Free Exercise clauses protect."

The third basic concept is local control. The act does not limit the authority of the school to maintain order and discipline or to protect the well-being of students and faculty.

Student missionaries

Allowing students to express their religious beliefs in schools, or

initiate and run religious clubs in schools, however, can create circumstances that make other students

uncomfortable. Moreover, going through students provides a pathway for churches and outside religious

organizations to enter the school doors. "Where students get encouragement or support doesn't matter,"

says Haynes. "Groups think it's their mission to convert students and schools are easy prey." And, AU's

Smith says this is a growing problem. "There's a large push for the hard right evangelical groups to

retake public schools and utilize them as mission fields."

Indeed, according to Rabbi Greene, one of the largest evangelical churches in Atlanta's northern suburbs, the Johnson Ferry Baptist Church, even provides literature to its young members about "how to approach your Jewish friends." He calls the effort "love bombing." Rabbi Shalom Lewis of Congregation Etz Chaim, which isn't far from Johnson Ferry Baptist Church, agrees that "they are very aggressive in their proselytizing and will teach Christianity to anyone who will listen. One of my former Hebrew School students came to me recently and said he accepted Christ; he's confused."

The Temple's Rabbi Peter S. Burg says he generally has a couple of students a year come to him with concerns that their Christian friends are trying to proselytize them. "I can usually resolve this by talking to our students directly and help them understand how to confront the situation. I have, on lesser occasions, called the principals and asked them to intervene. They usually do try to resolve the situation as they don't want a rabbi upset at them."

Resisting evangelism

When students feel harassed by their evangelical friends, instead of

taking their complaints to rabbis, the ACLU, the ADL or Americans United, sometimes the parents choose

to move their children to private schools or the entire family moves out of the district, says ACLU's

Seagraves.

There are other ways to fight back. As Chabad of Cobb Rabbi Ephrain Silverman states: "The best defense is a good offense." He is one of the Atlanta area rabbis who have worked with the Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta to help students establish Jewish clubs in their schools.

Jane started a Jewish Student Union in her school when she was a sophomore. "At first we were given a teacher's closet in which to meet. We didn't have many kids. We were up against the Fellowship of Christian Athletes that had 100 to 200 student members."

To counter the Christian influence in public schools, Greene teaches a class in his temple on the Jewish understanding of Jesus. "I don't want to teach my folks to be afraid of Christians, but I do want to teach our kids to feel good about being Jewish." He's been teaching the class to juniors and seniors, but in view of the fact that proselytizing is occurring even in middle schools today, Greene says, "I'm starting to consider teaching the class earlier, perhaps to 8th or 9th graders."

One hopeful sign: A former Cobb County, Georgia, high school student, now living in New York, reported that she recently visited the Museum of Natural History. There, in a display case, was a copy of her former biology textbook, along with the prominent, now banned, sticker claiming that evolution is only a theory. She saw it as a victory of sorts. A symbol of religion's encroachment into the public schools was now relegated to a museum.